Guess how many home runs ?

A lot. I will divulge later on. Mays was maybe the best fielder of the three. Killebrew maybe the most clutch. Mantle, the best switch hitter and also a damn fine base runner, apologies to Willie.

It doesn't matter how many they hit, it matters how they hit them.

All these hitters had sweet swings,

and all has Hall of Fame careers.

Killebrew was the pure slugger, Willie Mays the pure hitter, and Mickey Mantle was pure genius.

I don't care how many home runs each of them got, but to be fair, Mays hit 660, Killebrew hit 573, and Mickey Mantle hit 536 long balls.

In 68 , we had quite a year, the Hawk led the AL in Rib Eyes, just a few more than Frank Howard and quite a few more than 3rd place Jim Northrup of the Tigers.

Saturday, October 28, 2017

Monday, April 24, 2017

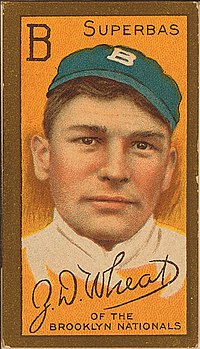

Zach Wheat

Born in Hamilton, Missouri,

he was the son of Basil and Julia Wheat. His father was of English

descent and his mother was full-blooded Cherokee. Wheat began his

professional baseball career in 1906 for Enterprise in the Kansas League, followed by Wichita in 1907, Shreveport Pirates of the Texas League in 1908, and finally, to round out his minor league career, he played for the Mobile Sea Gulls of the Southern Association in 1909. It was during that 1909 season that the Brooklyn Superbas of the National League purchased Wheat for $1200, and he made his Major League debut in September.

He batted with a corkscrew type of swing, and held his hands down near

the end of the bat, unlike most hitters during his time, a time noted as

the "Dead Ball Era". Even with his consistent high levels of hitting, he was also noted for his graceful and stylish defense.

Wheat played his first full season in 1910. He played every game for the Superbas that season as the regular left fielder, leading the league in games played. He batted .284 that season, the second-lowest average of his career, which led the team, and was among the league leaders in hits, doubles, and triples. It was in 1911 that his reputation as a slugger began to take hold. Along with hitting .287, he finished eighth in the league with 13 triples, and slugged five home runs. In an era when players rarely hit double-digit home runs for a season, five was enough for people to take notice

Wheat continued his steady and consistent climb up the batting charts in 1912, hitting .305, and finished the season among the league leaders in home runs and slugging percentage.[1] Over the next four seasons, he continued to be among the leaders of many offensive categories; such as home runs, batting average, slugging, hits, doubles, triples, and RBIs. It was during the 1912 season that Wheat married Daisy Kerr Forsman, and she became his default agent, encouraging him to hold out for a better contract each season. Players in his day signed one-year contracts before every season. Each time he held out, he received more money, the club not wanting to lose one of its best players and the team's most popular player.

His tactic of threatening to hold out served him well during throughout his career, including during the World War I era, when he raised and sold mules to the United States Army as pack animals. He claimed that he did so well, that he didn't need to play during the summer. The team, fearing that they might lose a great player during the prime of his career, would succumb to his demands every year.

In 1916, he topped off the string of seasons with a finish in the top ten in all the above categories, topping the league in total bases and slugging.] He also had a career-high hitting streak, which reached 29 games The Brooklyn Robins won the National League pennant that season. In the World Series, they faced the Boston Red Sox, which had the formidable pitching rotation of Ernie Shore, Dutch Leonard, Carl Mays, and Babe Ruth. The Red Sox won the series four games to one, holding the Robins to a .200 batting average, and Wheat to a paltry .211.

During the 1917 and 1918 seasons, Wheat hit well, but missed many games due to injuries. He had tiny feet, size 5, and this is believed to be the cause of the many nagging ankle injuries that caused to miss many games in his career. He did, however, lead the league in batting average for the only time in his career with a .335 batting average, his highest average up to that point. Interestingly, for a player known as a slugger, and consistently in the top ten in most offensive categories including home runs, he hit zero that season, and just one the season prior.

Starting in 1919, Wheat returned to the league slugging leaders once again, as the baseball began to become livelier, proved by the offensive output by the likes of Ruth, and Rogers Hornsby. The Robins made their second World Series appearance in 1920, this time facing off against the Cleveland Indians. The Robins lost this series as well, 5 games to 2, although Wheat's hitting greatly improved this time around, batting .333. Wheat's statistics climbed during this new live era of baseball, reaching double-digit home runs for the first time with 14 in 1921, and again three more times in the next four years. Wheat hit .320 or higher every season from 1920 through 1925, topping out with .375 in consecutive seasons. He failed to lead the league in hitting those two seasons, not getting enough at bats in 1923 to qualify, and Hornsby topped the league with .384,] and in 1924, his .375 finished a distant second to Hornsby's .424.

A subtle, but longstanding friction existed between Wheat and his manager, future Hall of Famer Wilbert Robinson. The friction reportedly stemmed from Robinson's belief that Wheat seemed to pursue the manager's job behind his back. When owner Charles Ebbets died in 1925, new team president Ed McKeever reassigned Robinson into the front office and named Wheat as player-manager. Newspapers confirm that he managed the Dodgers for two weeks. McKeever caught pneumonia at Ebbets' funeral, and died soon afterward, and Robinson quickly returned to the managers position. As it turned out, Wheat never again managed in the majors, much to his disappointment. To add insult to injury, Wheat's 1925 managerial stint never made it into the official records. In 1931, Steve McKeever, Ed's brother, hired Wheat as a coach, leading to widespread speculation that Zack was being groomed for the manager's spot, threatening Robinson's job for a second time in seven years, and he treated his former star as coldly as ever.

Wheat was signed by the Philadelphia Athletics after his release from Brooklyn in 1927. After the season, he was released again; this time he signed and played for the minor league Minneapolis Millers of the American Association. He played very little that season due to a heel injury, and retired from playing for good following the season.He still holds the Dodger franchise records for hits, doubles, triples and total bases.

vehicle ,

when he crashed and nearly died. Wheat spent five months in hospital

after the accident, and after he was discharged, he moved his family to Sunrise Beach, Missouri, a resort town on the Lake of the Ozarks, to recuperate. It was here that he opened a 46-acre (190,000 m2) hunting and fishing resort.

Wheat was first voted into the Baseball Hall of Fame by the Veterans Committee in 1957, but could not be inducted, due to the fact that he had not been officially retired for the required 30 years. In 1959, the committee unanimously elected him. In 1981, Lawrence Ritter and Donald Honig included him in their book The 100 Greatest Baseball Players of All Time. In 2006, the stretch of Route 13 that runs through Caldwell County, Missouri was named the Zach Wheat Memorial Highway.

Due to his Cherokee ancestry, Wheat was featured in "Baseball's League

of Nations: A Tribute to Native Americans in Baseball", a 2008 exhibit

at the Iroquois Indian Museum in Howes Cave, N.Y.

Wheat played his first full season in 1910. He played every game for the Superbas that season as the regular left fielder, leading the league in games played. He batted .284 that season, the second-lowest average of his career, which led the team, and was among the league leaders in hits, doubles, and triples. It was in 1911 that his reputation as a slugger began to take hold. Along with hitting .287, he finished eighth in the league with 13 triples, and slugged five home runs. In an era when players rarely hit double-digit home runs for a season, five was enough for people to take notice

Wheat continued his steady and consistent climb up the batting charts in 1912, hitting .305, and finished the season among the league leaders in home runs and slugging percentage.[1] Over the next four seasons, he continued to be among the leaders of many offensive categories; such as home runs, batting average, slugging, hits, doubles, triples, and RBIs. It was during the 1912 season that Wheat married Daisy Kerr Forsman, and she became his default agent, encouraging him to hold out for a better contract each season. Players in his day signed one-year contracts before every season. Each time he held out, he received more money, the club not wanting to lose one of its best players and the team's most popular player.

His tactic of threatening to hold out served him well during throughout his career, including during the World War I era, when he raised and sold mules to the United States Army as pack animals. He claimed that he did so well, that he didn't need to play during the summer. The team, fearing that they might lose a great player during the prime of his career, would succumb to his demands every year.

Zack Wheat baseball card, 1911 Gold Borders (T205)

During the 1917 and 1918 seasons, Wheat hit well, but missed many games due to injuries. He had tiny feet, size 5, and this is believed to be the cause of the many nagging ankle injuries that caused to miss many games in his career. He did, however, lead the league in batting average for the only time in his career with a .335 batting average, his highest average up to that point. Interestingly, for a player known as a slugger, and consistently in the top ten in most offensive categories including home runs, he hit zero that season, and just one the season prior.

Starting in 1919, Wheat returned to the league slugging leaders once again, as the baseball began to become livelier, proved by the offensive output by the likes of Ruth, and Rogers Hornsby. The Robins made their second World Series appearance in 1920, this time facing off against the Cleveland Indians. The Robins lost this series as well, 5 games to 2, although Wheat's hitting greatly improved this time around, batting .333. Wheat's statistics climbed during this new live era of baseball, reaching double-digit home runs for the first time with 14 in 1921, and again three more times in the next four years. Wheat hit .320 or higher every season from 1920 through 1925, topping out with .375 in consecutive seasons. He failed to lead the league in hitting those two seasons, not getting enough at bats in 1923 to qualify, and Hornsby topped the league with .384,] and in 1924, his .375 finished a distant second to Hornsby's .424.

A subtle, but longstanding friction existed between Wheat and his manager, future Hall of Famer Wilbert Robinson. The friction reportedly stemmed from Robinson's belief that Wheat seemed to pursue the manager's job behind his back. When owner Charles Ebbets died in 1925, new team president Ed McKeever reassigned Robinson into the front office and named Wheat as player-manager. Newspapers confirm that he managed the Dodgers for two weeks. McKeever caught pneumonia at Ebbets' funeral, and died soon afterward, and Robinson quickly returned to the managers position. As it turned out, Wheat never again managed in the majors, much to his disappointment. To add insult to injury, Wheat's 1925 managerial stint never made it into the official records. In 1931, Steve McKeever, Ed's brother, hired Wheat as a coach, leading to widespread speculation that Zack was being groomed for the manager's spot, threatening Robinson's job for a second time in seven years, and he treated his former star as coldly as ever.

Wheat was signed by the Philadelphia Athletics after his release from Brooklyn in 1927. After the season, he was released again; this time he signed and played for the minor league Minneapolis Millers of the American Association. He played very little that season due to a heel injury, and retired from playing for good following the season.He still holds the Dodger franchise records for hits, doubles, triples and total bases.

Post-career

After Wheat retired from baseball, he moved back to his 160-acre (0.65 km2) farm in Polo, Missouri, until the Great Depression forced him to sell it in 1932. He moved to Kansas City, Missouri, where he operated a bowling alley with Cotton Tierney.[4][10] He later became a police officer. It was during his duties as an officer in 1936, that he was chasing a fleeing felon in his

One of the grandest guys ever to wear a baseball uniform, one of the

greatest batting teachers I have seen, one of the truest pals a man ever

(had) and one of the kindliest men God ever created.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)